Bayes|Chapter 2

Chapter 2 - The Subjective Worlds of Frequentist and Bayesian Statistics

频率学派和贝叶斯统计的主观世界

2.1. Chapter Mission Statement

At the end of this chapter, the reader will understand the purpose of statistical inference, as well as recognise the similarities and differences between Frequentist and Bayesian inference. We also introduce the most important theorem in modern statistics: Bayes’ Theorem.

在本章的最后,读者将了解统计推断的目的,以及认识到频率论和贝叶斯推断之间的异同。 我们还介绍了现代统计学中最重要的定理:贝叶斯定理。

2.2. Chapter Goals

As data scientists, we aim to build predictive models to understand complex phenomena. As a first approximation, we typically disregard those parts of the system that are not directly of interest. This deliberate omission of information makes these models statistical rather than deterministic because there are some aspects of the system about which we are uncertain.

作为数据科学家,我们的目标是构建预测模型来理解复杂的现象。 我们通常首先会尝试忽略系统中不直接感兴趣的那些部分。 这种故意的信息遗漏使得这些模型具有统计性而不是确定性,因为我们对系统的某些方面是不确定的。

There are two distinct approaches to statistical modelling: Frequentist (also known as Classical inference) and Bayesian inference. This chapter explains the similarities between these two approaches and, importantly, indicates where they differ substantively. Usually, it is straightforward to calculate the probability of obtaining different data samples if we know the process that generated the data in the first place.

统计建模有两种不同的方法:频率学派(也称为经典推断)和贝叶斯推断。 本章解释了这两种方法之间的相似之处,重要的是,指出了它们的实质性区别。 通常,如果我们首先知道生成数据的过程,就可以直接计算获得不同数据样本的概率。

For example, if we know that a coin is fair, then we can calculate the probability of it landing heads up (the probability equals 1/2). However, we typically do not have perfect knowledge of these processes, and it is the goal of statistical inference to derive estimates of the unknown characteristics, or parameters, of these mechanisms.

例如,如果我们知道一枚硬币是公平的,那么我们可以计算出它正面朝上落地的概率(概率等于 1/2)。 然而,我们通常不具有这些过程的完美知识,并且统计推断的目标是推导出这些机制的未知特征或参数的估计。

In our coin example, we might want to determine its bias towards heads on the basis of the results of a few coin throws. Bayesian statistics allows us to go from what is known – the data (the results of the coin throw here) – and extrapolate backwards to make probabilistic statements about the parameters (the underlying bias of the coin) of the processes that were responsible for its generation.

在我们的硬币例子中,我们可能希望根据几次抛硬币的结果来确定它朝正面的倾向。 贝叶斯统计允许我们从已知的数据(掷硬币的结果)出发,向后推断出导致硬币产生的过程的参数(硬币的潜在倾向)的概率陈述。

In Bayesian statistics, this inversion process is carried out by application of Bayes’ rule, which is introduced in this chapter. It is important to have a good understanding of this rule, and we will spend some time throughout this chapter and Part II developing an understanding of the various constituent components of the formula.

在贝叶斯统计中,这种反演过程是通过应用贝叶斯规则来实现的,这一章将介绍。 很重要的一点是,我们要很好地理解这条规则,在本章和第二部分中,我们将花一些时间来理解公式的各个组成部分。

2.3. Bayes' Theorem - Allowing us to go From the Effect back to its Cause (从结果回到原因)

Suppose that we know that a casino is crooked(不正当的赌场) and uses a loaded die(灌了铅的骰子) with a probability of rolling a 1, that is $\frac{1}{3}=2 \times \frac{1}{6}$, twice its unbiased value. We could then calculate the probability that we roll two 1s in a row: $$Pr(1,1| \text{crooked casino}) = \frac{1}{3} \times \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{9}$$

In this case, we have presupposed a cause – the casino being crooked – to derive the probability of a particular effect – rolling two consecutive 1s. In other words, we have calculated Pr(effect | cause). 在这种情况下,我们已经预先假定了一个原因 —— 赌场是不正当的 —— 来推导出一个特定结果的概率 —— 连续掷出两个 1。 换句话说,我们已经计算知道原因的前提下,特定结果的概率。

Until the latter half of the seventeenth century, probability theory was chiefly used as a method to calculate gambling odds, in a similar vein to our current example. It was viewed as a dirty subject, not worthy of the attention of the most esteemed mathematicians. This perspective began to change with the intervention of the English Reverend Thomas Bayes, and slightly later and more famously (at the time at least), with the work done by the French mathematician Pierre Simon Laplace.

直到 17 世纪下半叶,概率论主要被用作计算赌博赔率的方法,与我们现在的例子类似。 它被视为一个肮脏的话题,没有被受人尊敬的数学家注意。 随着英国牧师托马斯贝叶斯的介入,这种观点开始发生变化。在这之后,随着法国数学家皮埃尔·西蒙·拉普拉斯的工作,这种观点变得更加有名(至少在当时是这样)。

They realised that it is possible to move in the opposite direction – to go from effect back to cause:

他们意识到,可以反其道而行之 —— 从结果回到原因:

$$Pr(\text{effect}|\text{cause}) \stackrel{Bayes’thm}{\longrightarrow} Pr(\text{effect}|\text{cause})$$

In order to take this leap, however, it was necessary to discover a rule, which later became known as Bayes’ rule or theorem. This can be written:

$$Pr(\text{effect}|\text{cause}) = \frac{Pr(\text{effect}|\text{cause}) \times Pr(\text{cause})}{Pr(\text{effect})}$$

This process where we go from an effect back to a cause is the essence of inference. Bayes’ rule is central to the Bayesian approach to statistical inference.

我们从结果回到原因的过程是推理的本质。贝叶斯定理是统计推断中贝叶斯方法的核心。

2.4 The purpose of statistical inference (统计推断的目的)

How much does a particular drug affect a patient’s condition? What can an average student earn after obtaining a college education? Will the Democrats win the next US presidential election? In life, we develop theories and use these to make predictions, but testing those theories is not easy. Life is complicated, and it is often impossible to exactly isolate the parts of a system which we want to examine. The outcome of history is determined by a complex nexus of interacting elements, each of which contributes to the reality that we witness.

一种特定的药物对患者病情的影响有多大? 一个普通的学生在接受大学教育后能挣多少钱? 民主党会赢得下届美国总统大选吗? 在生活中,我们发展理论,并利用这些理论做出预测,但测试这些理论并不容易。 生活是复杂的,要把我们想研究的系统的各个部分准确地分离出来,往往是不可能的。历史的结果是由相互作用的因素的复杂关系决定的,其中每一个因素都对我们所见证的现实作出贡献。

In the case of a drug trial, we may not be able to control the diets of participants and are certainly unable to control for their idiosyncratic metabolisms, both of which could impact the results we observe. There are a range of factors which affect the wage that an individual ultimately earns, of which education is only one. The outcome of the next US presidential election depends on party politics, the performance of the incumbent government and the media’s portrayal of the candidates.

在药物试验的情况下,我们可能无法控制参与者的饮食,当然也无法控制他们的特异质代谢,这两种情况都可能影响我们观察到的结果。 影响个人最终所得工资的因素有很多,教育只是其中之一。 下届美国总统大选的结果取决于政党政治、现任政府的表现以及媒体对候选人的描绘。

In life, noise obfuscates the signal. What we see often appears as an incoherent mess that lacks any appearance of logic. This is why it is difficult to make predictions and test theories about the world. It is like trying to listen to a classical orchestra which is playing on the side of a busy motorway, while we fly overhead in a plane. Statistical inference allows us to focus on the music by separating the signal from the noise. We will hear ‘Nessun Dorma’ played!

在生活中,噪音会使信号变得模糊。 我们所看到的往往是一团混乱,缺乏逻辑。 这就是为什么很难对世界做出预测和检验理论的原因。 这就像我们坐在忙碌的高速公路旁听古典管弦乐队演奏,一架飞机还从头顶飞过。 统计推断使我们能够通过将信号与噪声分离来专注于音乐。 我们将听到“今夜无人入睡”的演奏!

Statistical inference is the logical framework which we can use to trial our beliefs about the noisy world against data. We formalise our beliefs in models of probability. The models are probabilistic because we are ignorant of many of the interacting parts of a system, meaning we cannot say with certainty whether something will, or will not, occur. Suppose that we are evaluating the efficacy of a drug in a trial. Before we carry out the trial, we might believe that the drug will cure 10% of people with a particular ailment. We cannot say which 10% of people will be cured because we do not know enough about the disease or individual patient biology to say exactly whom. Statistical inference allows us to test this belief against the data we obtain in a clinical trial.

统计推理是一个逻辑框架,我们可以用它来对照数据来检验我们对嘈杂世界的信念。我们在概率模型中正式确定了我们的信念。这些模型是概率性的,因为我们对一个系统的许多相互作用的部分一无所知,这意味着我们不能肯定地说某件事情是否会发生或不会发生。假设我们在一项试验中评估一种药物的疗效。在我们进行试验之前,我们可能相信这种药物会治愈 10%的人的某种疾病。我们不能说哪 10%的人将被治愈,因为我们对疾病或个别病人的身体情况了解不够,无法准确说出是谁。统计推理使我们能够根据临床试验中获得的数据来检验这一信念。

There are two predominant schools of thought for carrying out this process of inference: Frequentist and Bayesian. Although this book is devoted to the latter, we will now spend some time comparing the two approaches so that the reader is aware of the different paths taken to their shared goal.

在进行这一推理过程中,有两个主要的思想流派:频繁学派和贝叶斯派。尽管本书是专门讨论后者的,但我们现在将花一些时间来比较这两种方法,以便读者了解实现其共同目标的不同路径。

2.5 The world according to Frequentists (频率学派视角下的世界)

In Frequentist (or Classical) statistics, we suppose that our sample of data is the result of one of an infinite number of exactly repeated experiments. The sample we see in this context is assumed to be the outcome of some probabilistic process. Any conclusions we draw from this approach are based on the supposition that events occur with probabilities, which represent the long-run frequencies with which those events occur in an infinite series of experimental repetitions. For example, if we flip a coin, we take the proportion of heads observed in an infinite number of throws as defining the probability of obtaining heads. Frequentists suppose that this probability actually exists, and is fixed for each set of coin throws that we carry out. The sample of coin flips we obtain for a fixed and finite number of throws is generated as if it were part of a longer (that is, infinite) series of repeated coin flips.

在频率学派(或经典)统计学中,我们假设我们的数据样本是无限次精确重复实验的结果之一。在这种情况下,我们看到的样本被假定为某种概率过程的结果。我们从这种方法得出的任何结论都是基于这样的假设:事件发生的概率,代表了这些事件在无限次的实验重复中发生的长期频率。例如,如果我们抛出一枚硬币,我们把在无限次抛掷中观察到的正面比例作为定义获得正面的概率。频率学派认为,这个概率实际上是存在的,而且对于我们进行的每一组抛掷硬币都是固定的。我们在固定和有限的抛掷次数中获得的抛掷硬币的样本,就像它是更长(即无限)的重复抛掷硬币系列的一部分一样产生。

In Frequentist statistics the data are assumed to be random and results from sampling from a fixed and defined population distribution. For a Frequentist the noise that obscures the true signal of the real population process is attributable to sampling variation – the fact that each sample we pick is slightly different and not exactly representative of the population.

在频率学派视角下的统计学中,数据被假定为随机的,是从一个固定的、确定的总体分布中抽样得到的结果。对于频率学派来说,掩盖真实总体过程的真实信号的噪音可归因于抽样变化–我们挑选的每个样本都略有不同,并不完全代表人口的事实。

We may flip our coin 10 times, obtaining 7 heads even if the long-run proportion of heads is 1/2. To a Frequentist, this is because we have picked a slightly odd sample from the population of infinitely many repeated throws. If we flip the coin another 10 times, we will likely get a different result because we then pick a different sample.

我们可能投掷 10 次硬币,即使硬币正面的长期比例是 1/2,仍然有可能获得 7 个正面。对于频率学派来说,这是因为我们从无限多次重复抛掷的总体中挑选了一个稍微奇怪的样本。如果我们再掷 10 次硬币,很可能会得到不同的结果,因为我们选择了不同的样本。

2.6 The world according to Bayesians(贝叶斯学派视角下的世界)

Bayesians do not imagine repetitions of an experiment in order to define and specify a probability. A probability is merely taken as a measure of certainty in a particular belief. For Bayesians the probability of throwing a ‘heads’ measures and quantifies our underlying belief that before we flip the coin it will land this way.

贝叶斯主义者不会为了定义和指定概率而想象一个实验的多次重复。概率只是被看作是对某一特定信念的确定性的衡量。对于贝叶斯主义者来说,投掷 “正面"的概率衡量和量化了我们在抛出硬币之前对于落地结果的基本信念。

In this sense, Bayesians do not view probabilities as underlying laws of cause and effect. They are merely abstractions which we use to help express our uncertainty. In this frame of reference, it is unnecessary for events to be repeatable in order to define a probability. We are thus equally able to say, ‘The probability of a heads is 0.5’ or ‘The probability of the Democrats winning the 2020 US presidential election is 0.75’. Probability is merely seen as a scale from 0, where we are certain an event will not happen, to 1, where we are certain it will.

在这个意义上,贝叶斯主义者并不把概率看作是因果关系的基本规律。它们只是我们用来帮助表达我们的不确定性的抽象概念。在这个参考框架中,为了定义一个概率,事件没有必要是可重复的。因此,我们同样可以说,“抛一枚硬币正面的概率是 0.5 “或 “民主党赢得 2020 年美国总统选举的概率是 0.75”。概率只是被看作是一个从 0 到 1 的刻度,在这个刻度上我们确定一个事件不会发生,而在这个刻度上我们确定它会发生。

Figure 2.1.

A statement such as ‘The probability of the Democrats winning the 2020 US presidential election is 0.75’ is hard to explain using the Frequentist definition of a probability. There is only ever one possible sample – the history that we witness – and what would we actually mean by the ‘population of all possible US elections which happen in the year 2020’?

像“民主党赢得 2020 年美国总统大选的概率是 0.75”这样的陈述很难用频率视角对概率的定义来解释。 只有一个可能的样本——我们所见证的历史——我们所说的“2020 年所有可能发生的美国选举的人口”实际上意味着什么?

For Bayesians, probabilities are seen as an expression of subjective beliefs, meaning that they can be updated in light of new data. The formula invented by the Reverend Thomas Bayes provides the only logical manner in which to carry out this updating process. Bayes’ rule is central to Bayesian inference whereby we use probabilities to express our uncertainty in parameter values after we observe data.

对于贝叶斯主义者来说,概率被看作是主观信念的表达,这意味着它们可以根据新的数据进行更新。 由托马斯贝叶斯牧师发明的公式提供了进行这种更新过程的唯一合乎逻辑的方式。贝叶斯定理是贝叶斯推断的核心,我们在观察数据后使用概率来表示参数值的不确定性。

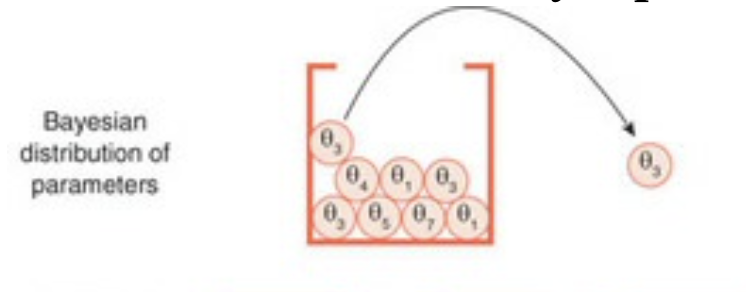

Bayesians assume that, since we are witness to the data, it is fixed, and therefore does not vary. We do not need to imagine that there are an infinite number of possible samples, or that our data are the undetermined outcome of some random process of sampling. We never perfectly know the value of an unknown parameter (for example, the probability that a coin lands heads up). This epistemic uncertainty (namely, that relating to our lack of knowledge) means that in Bayesian inference the parameter is viewed as a quantity that is probabilistic in nature.

贝叶斯主义者假设,因为我们观察到的数据是固定的,因此不会变化。我们不需要想象有无限多个可能的样本,或者我们的数据是某种随机抽样过程的不确定结果。 我们永远不可能完全知道一个未知参数的值(例如,硬币正面朝上落地的概率)。 这种认识上的不确定性(即与我们缺乏知识有关的不确定性)意味着,在贝叶斯推理中,参数被视为一个本质上是概率性的量。

We can interpret this in one of two ways. On the one hand, we can view the unknown parameter as truly being fixed in some absolute sense, but our beliefs are uncertain, and thus we express this uncertainty using probability. In this perspective, we view the sample as a noisy representation of the signal and hence obtain different results for each set of coin throws. On the other hand, we can suppose that there is not some definitive true, immutable probability of obtaining a heads, and so for each sample we take, we unwittingly get a slightly different parameter.

我们可以用两种方式来解释这一点。 一方面,我们可以认为未知参数在某种绝对意义上确实是固定的,但我们的信念是不确定的,因此我们用概率来表达这种不确定性。 从这个角度来看,我们将样本视为信号的噪声表示,因此获得每组硬币投掷不同的结果。 另一方面,我们可以假设不存在某个确定的、真实的、不变的概率来获得正面,因此对于我们所取的每一个样本,我们无意中得到了一个略有不同的参数。

Here we get different results from each round of coin flipping because each time we subject our system to a slightly different probability of its landing heads up. This could be because we altered our throwing technique or started with the coin in a different position. Although these two descriptions are different philosophically, they are not different mathematically, meaning we can apply the same analysis to both.

在这里,我们从每一轮抛硬币中得到不同的结果,因为每一次我们都让我们的系统接受一个稍微不同的概率,它的落地正面朝上。 这可能是因为我们改变了投掷方法,或者是从不同的位置开始投掷硬币。 虽然这两种描述在哲学上是不同的,但在数学上并没有不同,这意味着我们可以对两者应用相同的分析。

2.7 Do parameters actually exist and have a point value?

For Bayesians, the parameters of the system are taken to vary, whereas the known part of the system – the data – is taken as given. Frequentist statisticians, on the other hand, view the unseen part of the system – the parameters of the probability model – as being fixed and the known parts of the system – the data – as varying. Which of these views you prefer comes down to how you interpret the parameters of a statistical model.

对于贝叶斯主义者来说,系统的参数被认为是变化的,而系统的已知部分–数据–被认为是给定的。另一方面,频率学家认为系统的不可见部分–概率模型的参数–是固定的,而系统的已知部分–数据–是变化的。你喜欢哪一种观点,取决于你如何解释统计模型的参数。

In the Bayesian approach, parameters can be viewed from two perspectives. Either we view the parameters as truly varying, or we view our knowledge about the parameters as imperfect. The fact that we obtain different estimates of parameters from different studies can be taken to reflect either of these two views.

在贝叶斯方法中,可以从两个角度来看待参数。要么我们将参数视为真正的变化,要么我们将关于参数的知识视为不完善。我们从不同的研究中获得不同的参数估计值,这一事实可以反映这两种观点中的任何一种。

In the first case, we understand the parameters of interest as varying – taking on different values in each of the samples we pick (see the top panel of Figure 2.2). For example, suppose that we conduct a blood test on an individual in two consecutive weeks, and represent the correlation between the red and white cell count as a parameter of our statistical model. Due to the many factors that affect the body’s metabolism, the count of each cell type will vary somewhat randomly, and hence the parameter value may vary over time.

在第一种情况下,我们把感兴趣的参数理解为是变化的–在我们挑选的每个样本中都有不同的值(见图 2.2)。例如,假设我们在连续两周内对一个人进行验血,并将红细胞和白细胞计数的相关性表示为我们统计模型的一个参数。由于影响人体新陈代谢的因素很多,每种细胞的数量会有一定程度的随机变化,因此参数值可能会随时间变化。

In the second case, we view our uncertainty over a parameter’s value as the reason we estimate slightly different values in different samples. This uncertainty should, however, decrease as we collect more data (see the middle panel of Figure 2.2). Bayesians are more at ease in using parameters as a means to an end – taking them not as real immutable constants, but as tools to help make inferences about a given situation.

在第二种情况下,我们认为我们对一个参数值的不确定性是我们在不同的样本中估计的数值略有不同的原因。然而,这种不确定性应该随着我们收集更多的数据而减少(见图 2.2 的中间部分)。贝叶斯主义者更愿意把参数作为达到目的的手段–不把它们当作真正的不可改变的常数,而是当作帮助对特定情况进行推断的工具。

The Frequentist perspective is less flexible and assumes that these parameters are constant, or represent the average of a long run – typically an infinite number – of identical experiments. There are occasions when we might think that this is a reasonable assumption. For example, if our parameter represented the probability that an individual taken at random from the UK population has dyslexia, it is reasonable to assume that there is a true, or fixed, population value of the parameter in question. While the Frequentist view may be reasonable here, the Bayesian view can also handle this situation. In Bayesian statistics these parameters can be assumed fixed, but that we are uncertain of their value (here the true prevalence of dyslexia) before we measure them, and use a probability distribution to reflect this uncertainty.

频率学派的观点不那么灵活,它假定这些参数是恒定的,或者代表了一个长期的–通常是无限多的–相同实验的平均数。在有些情况下,我们可能认为这是一个合理的假设。例如,如果我们的参数代表了从英国人口中随机抽取的个体患有阅读障碍的概率,那么假设相关参数有一个真实或固定的人口值是合理的。虽然频率学家的观点在这里可能是合理的,但贝叶斯观点也可以处理这种情况。在贝叶斯统计学中,可以假设这些参数是固定的,但我们在测量它们之前对它们的价值(这里指阅读障碍的真实流行率)是不确定的,并使用概率分布来反映这种不确定性。

Problems of the Frequentist View

But there are circumstances when the Frequentist view runs into trouble. When we are estimating parameters of a complex distribution, we typically do not view them as actually existing. Unless you view the Universe as being built from mathematical building blocks, then it seems incorrect to assert that a given parameter has any deeper existence than that with which we endow it. The less restrictive Bayesian perspective here seems more reasonable.

但在有些情况下,频率学派的观点会遇到麻烦。当我们在估计一个复杂分布的参数时,我们通常不认为它们是实际存在的。除非你认为宇宙是由数学模块构成的,那么断言一个给定的参数比我们赋予它的参数有任何更深的存在似乎是不正确的。这里限制性较小的贝叶斯观点似乎更合理。

The Frequentist view of parameters as a limiting value of an average across an infinity of identically repeated experiments (see the bottom panel of Figure 2.2) also runs into difficulty when we think about one-off events. For example, the probability that the Democrat candidate wins in the 2020 US election cannot be justified in this way, since elections are never rerun under the exact same conditions.

当我们考虑一次性事件时,频率学派将参数视为无数次相同重复实验的平均值的极限值也遇到了困难。例如,民主党候选人在 2020 年美国大选中获胜的概率就不能用这种方式来证明,因为选举永远不会在完全相同的条件下重新(重复)进行。

2.8 Frequentist and Bayesian inference 20

The Bayesian inference process is the only logical and consistent way to modify our beliefs to account for new data. Before we collect data we have a probabilistic description of our beliefs, which we call a prior. We then collect data, and together with a model describing our theory, Bayes’ formula allows us to calculate our post-data or posterior belief:

贝叶斯推理过程是修改我们的信念以说明新数据的唯一合乎逻辑和一致的方法。在我们收集数据之前,我们对我们的信念有一个概率性的描述,我们称之为先验。然后我们收集数据,再加上描述我们理论的模型,贝叶斯公式允许我们计算出我们的后数据或后验信念:

$$prior + data \stackrel{model}{\longrightarrow} posterior $$

For example, suppose that we have a prior belief that a coin is fair, meaning that the probability of it landing heads up is 1⁄2. We then throw it 10 times and find that it lands heads up every time; this is our data. Bayes’ rule tells us how to combine the prior with the data to result in our updated belief that the coin is fair. Ignore for the moment that we have not explained the meaning of this mysterious prior, as we shall introduce this element properly in Section 2.9.2.

例如,假设我们有一个先验的信念,认为一枚硬币是公平的,也就是说,它落在正面的概率是 1/2。然后我们扔了 10 次,发现它每次都是正面朝上;这就是我们的数据。贝叶斯规则告诉我们如何将先验与数据结合起来,从而得出硬币是公平的这一最新信念。暂时忽略我们没有解释这个神秘的先验的含义,因为我们将在第 2.9.2 节中适当地介绍这个要素。

In inference, we want to draw conclusions based purely on the rules of probability. If we wish to summarise our evidence for a particular hypothesis, we describe this using the language of probability, as the ‘probability of the hypothesis given the data obtained’. The difficulty is that when we choose a probability model to describe a situation, it enables us to calculate the ‘probability of obtaining our data given our hypothesis being true’ – the opposite of what we want. This probability is calculated by accounting for all the possible samples that could have been obtained from the population, if the hypothesis were true. The issue of statistical inference, common to both Frequentists and Bayesians, is how to invert this probability to get the desired result.

在推理中,我们希望纯粹根据概率规则得出结论。如果我们想总结我们对某一特定假设的证据,我们就用概率语言来描述,即 “鉴于所获得的数据,该假设的概率”。困难在于,当我们选择一个概率模型来描述一种情况时,它使我们能够计算出 “在我们的假设为真的情况下获得数据的概率”–与我们想要的相反。这个概率是通过计算所有可能的样本来计算的,如果假设是真的话,这些样本可以从人口中获得。概率学派和贝叶斯学派共同面临的统计推断问题是如何反转这个概率以获得所需的结果。

2.9 Bayesian inference via Bayes’ rule 23

2.9.1. Likelihoods

2.9.2. Priors

2.9.3. The Denominator

2.9.4. Posteriors: the goal of Bayesian Inference

2.10 Implicit versus explicit subjectivity (内隐 vs 外显主观)

2.11 Chapter summary 27

2.12 Chapter outcomes 28

History

1. David Hume

In 1748, the Scottish philosopher David Hume dealt a serious blow to a fundamental belief of Christianity by publishing an essay on the nature of cause and effect. In it, Hume argues that ‘causes and effects are discoverable, not by reason, but by experience’. In other words, we can never be certain about the cause of a given effect.

1748 年,苏格兰哲学家大卫·休谟(David Hume)发表了一篇关于因果本质的文章,对基督教的一个基本信仰造成了严重打击。 在文章中,休谟认为,“原因和结果是可以发现的,不是通过理性,而是通过经验”。 换句话说,我们永远无法确定一个给定结果的原因。

For example, we know from experience that if we push a glass off the side of a table, it will fall and shatter, but this does not prove that the push caused the glass to shatter. It is possible that both the push and the shattering are merely correlated events, reflecting some third, and hitherto unknown, ultimate cause of both.

例如,我们从经验中知道,如果我们把一个玻璃杯从桌子的一边推下来,它就会掉下来并碎掉,但这并不能证明是推的原因导致了玻璃杯的碎掉。 有可能推力和粉碎只是两个相互关联的事件,反映了第三个、迄今未知的,两者的最终原因。

Hume’s argument was unsettling to Christianity because God was traditionally known as the First Cause of everything. The mere fact that the world exists was seen as evidence of a divine creator that caused it to come into existence. Hume’s argument meant that we can never deal with absolute causes; rather, we must make do with probable causes. This weakened the link between a divine creator and the world that we witness and, hence, undermined a core belief of Christianity.

休谟的论证令基督教感到不安,因为传统上上帝被认为是万物的第一因。 世界存在这一事实被看作是一个神圣的创造者使它得以存在的证据。 休谟的论证意味着我们永远不能处理绝对原因;相反,我们必须用可能的理由来应付。这削弱了神的创造者和我们所见证的世界之间的联系,因此,破坏了基督教的一个核心信仰。

Around this time the Reverend Thomas Bayes of Tunbridge Wells began to ponder whether there might be a mathematical approach to cause and effect.

大约在这个时候,托马斯·贝叶斯牧师开始思考是否有一种数学方法来解释因果关系。

2. Thomas Bayes

Thomas Bayes was born around 1701 to a Presbyterian minister, Joshua Bayes, who oversaw a chapel in London. The Presbyterian Church at the time was a religious denomination persecuted for not conforming to the governance and doctrine of the Church of England. Being a non- conformist, the young Bayes was not permitted to study for a university degree in England and so enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, where he studied theology. After university, Bayes was ordained as a minister of the Presbyterian Church by his clergyman father and began work as an assistant in his father’s ministry in London. Around 1734, Bayes moved south of London to the wealthy spa resort town of Tunbridge Wells and became minister of the Mount Sion chapel there.

托马斯·贝叶斯出生于 1701 年左右,父亲是长老会牧师约书亚·贝叶斯(Joshua Bayes),他在伦敦监管一座教堂。 当时的长老会是一个宗教派别,因不遵守英国国教的治理和教义而受到迫害。 作为一个不墨守成规的人,年轻的贝叶斯不被允许在英国攻读大学学位,因此就读于爱丁堡大学,在那里他学习神学。 大学毕业后,贝叶斯被他的父亲任命为长老会的牧师,并开始在他父亲在伦敦的事工中担任助理工作。1734 年左右,贝叶斯搬到了伦敦南部富有的温泉度假小镇唐桥井,并成为那里的锡安山教堂的牧师。

Around this time, Bayes began to think about how to apply mathematics, specifically probability theory, to the study of cause and effect (perhaps invigorated by the minerals in the spa town’s cold water). Specifically, Bayes wanted a mathematical way to go from an effect back to its cause.

大约在这个时候,贝叶斯开始思考如何应用数学,特别是概率论,来研究因果关系(也许是受到温泉镇冷水中的矿物质的激发)。 具体来说,贝叶斯想要一种数学方法来从结果追溯到原因。

To develop his theory, he proposed a thought experiment: he imagined attempting to guess the position of a ball on a table. Not perhaps the most enthralling of thought experiments, but sometimes clear thinking is boring. Bayes imagined that he had his back turned to the table, and asks a friend to throw a cue ball onto its surface (imagine the table is big enough that we needn’t worry about its edges). He then asks his friend to throw a second ball, and report to Bayes whether it landed to the left or right of the first. If the ball landed to the right of the first, then Bayes reasoned that the cue ball is more likely to be on the left-hand side of the table, and vice versa if it landed to its left. Bayes and his friend continue this process where, each time, his friend throws subsequent balls and reports which side of the cue ball his throw lands.

为了发展他的理论,他提出了一个思想实验:他想象着试图猜出球在桌子上的位置。 也许这不是最吸引人的思维实验,但有时清晰的思维是无聊的。 贝叶斯假设他背对着桌子,让一个朋友把一个白球扔到桌子上(假设桌子足够大,我们不必担心它的边缘)。 然后,他让他的朋友投第二个球,并向贝叶斯报告它是落在第一个球的左边还是右边。 如果球落在第一个球的右边,那么贝叶斯推断主球更有可能在桌子的左手边,反之亦然,如果它落在左手边。 贝叶斯和他的朋友继续这个过程,每次,他的朋友抛出后续的球,并报告他抛出的球落在主球的哪一边。

Bayes’ brilliant idea was that, by assuming all positions on the table were equally likely a priori, and using the results of the subsequent throws, he could narrow down the likely position of the cue ball on the table. For example, if all throws landed to the left of the cue ball, it was likely that the cue ball would be on the far right of the table. And, as more data (the result of the throws) was collected, he became more and more confident of the cue ball’s position. He had gone from an effect (the result of the throws) back to a probable cause (the cue ball’s position)!

贝叶斯的绝妙想法是,通过假设桌子上的所有位置都是先验概率相等的,并使用随后投掷的结果,他可以缩小主球在桌子上的可能位置。 例如,如果所有的投掷都落在主球的左边,那么主球很可能会在桌子的最右边。 而且,随着更多的数据(投掷的结果)被收集,他变得越来越有信心知道球的位置。 他已经从一个结果(投掷的结果)回到了一个可能的原因(主球的位置)!

Bayes’ idea was discussed by members of the Royal Society, but it seems that Bayes himself perhaps was not so keen on it, and never published this work. When Bayes died in 1761 his discovery was still languishing between unimportant memoranda, where he had filed it. It took the arrival of another, much more famous, clergyman to popularise his discovery.

贝叶斯的想法被英国皇家学会的成员讨论过,但似乎贝叶斯本人也许并不那么热衷于此,而且从未没有发表这项工作。 1761 年贝叶斯去世时,他的发现还在一些无关紧要的备忘录中徘徊,直到另一位更著名的牧师到来,他的发现才得以普及。

3. Richard Price

Richard Price was a Welsh minister of the Presbyterian Church, but was also a famous political pamphleteer, active in liberal causes of the time such as the American Revolution. He had considerable fans in America and communicated regularly with Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Indeed, his fame and adoration in the United States reached such levels that in 1781, when Yale University conveyed two degrees, it gave one to George Washington and the other to Price. Yet today, Price is primarily known for the help that he gave his friend Bayes.

理查德-普莱斯是长老会的一名威尔士牧师,但同时也是一名著名的政治传记作家,积极参加当时的自由主义事业,如美国革命。他在美国有相当多的粉丝,并定期与本杰明-富兰克林、约翰-亚当斯和托马斯-杰斐逊进行交流。事实上,他在美国的名气和崇拜达到了这样的程度,以至于 1781 年,耶鲁大学授予两个学位时,一个给了乔治-华盛顿,另一个给了普莱斯。然而今天,普莱斯主要是因为他给予他的朋友贝叶斯的帮助而闻名。

When Bayes died, his family asked his young friend Richard Price to examine his mathematical papers. When Price read Bayes’ work on cause and effect he saw it as a way to counter Hume’s attack on causation (using an argument not dissimilar to the Intelligent Design hypothesis of today), and realised it was worth publishing. He spent two years working on the manuscript – correcting some mistakes and adding references – and eventually sent it to the Royal Society with a cover letter of religious bent. Bayes for his (posthumous) part of the paper did not mention religion. The Royal Society eventually published the manuscript with the secular title, ‘An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances’. Sharon McGrayne – a historian of Bayes – argues that, by modern standards, Bayes’ rule should be known as the Bayes–Price rule, since Price discovered Bayes’ work, corrected it, realised its importance and published it.

贝叶斯去世后,他的家人请他的年轻朋友理查德-普莱斯(Richard Price)研究他的数学论文。当普莱斯读到贝叶斯关于因果关系的工作时,他认为这是一种反击休谟对因果关系的攻击的方式(使用的论据与今天的智能设计假说没什么不同),并意识到它值得出版。他花了两年时间来处理这份手稿–纠正一些错误并增加参考文献–最终将它寄给了皇家学会,并附上一封宗教倾向的封面信。贝叶斯为他的(遗作)部分论文没有提到宗教。皇家学会最终以世俗的标题出版了这份手稿:“解决机会学说问题的论文”。Sharon McGrayne–贝叶斯的历史学家–认为,按照现代标准,贝叶斯定理应该被称为贝叶斯-普莱斯定理,因为普莱斯发现了贝叶斯的工作,对其进行了修正,意识到其重要性并将其出版。

Given Bayes’ current notoriety, it is worth noting what he did not accomplish in his work. He did not actually develop the modern version of Bayes’ rule that we use today. He just used Newton’s notation for geometry to add and remove areas of the table. Unlike Price, he did not use the rule as proof for God, and was clearly not convinced by his own work since he failed to publish his papers. Indeed, it took the work of another, more notable, mathematician to improve on Bayes’ first step, and to elevate the status of inverse probability (as it was known at the time).

鉴于贝叶斯目前的恶名,值得注意的是他在工作中没有完成的事情。他实际上并没有发展出我们今天使用的现代版本的贝叶斯定理。他只是用牛顿的几何学符号来添加和删除表格的面积。与普莱斯不同的是,他没有用这个规则来证明上帝,而且显然没有被自己的工作所说服,因为他没有发表自己的论文。事实上,另一位更著名的数学家的工作才改进了贝叶斯的第一步,并提升了逆概率的地位(当时它被称为)。

4. Pierre Simon Laplace

Pierre Simon Laplace was born in 1749 in Normandy, France, into a house of respected dignitaries. His father, Pierre, owned and farmed the estates of Maarquis, and was Syndic (an officer of the local government) of the town of Beaumont. The young Laplace (like Bayes) studied theology for his degree at the University of Caen. There, his mathematical brilliance was quickly recognised by others, and Laplace realised that maths was his true calling, not the priesthood. Throughout his life, Laplace did important work in many fields including analysis, differential equations, planetary orbits and potential theory. He may also have even been the first person to posit the existence of black holes – celestial bodies whose gravity is so great that even light can’t escape. However, here, we are most interested in the work he did on inverse probability theory.

皮埃尔-西蒙-拉普拉斯 1749 年出生于法国诺曼底的一个受人尊敬的贵族家庭。他的父亲皮埃尔拥有 Maarquis 庄园并从事耕种,是博蒙镇当地政府的官员。年轻的拉普拉斯(和贝叶斯一样)在卡昂大学攻读神学学位。在那里,他的数学才华很快就被其他人认可,拉普拉斯意识到数学是他真正的使命,而不是神职。在他的一生中,拉普拉斯在许多领域做了重要的工作,包括分析、微分方程、行星轨道和位势论。他甚至可能是第一个提出黑洞存在的人–引力大到连光都无法逃脱的天体。然而,在这里,我们最感兴趣的是他在逆概率理论方面的工作。

Independently of Bayes, Laplace had already begun to work on a probabilistic way to go from effect back to cause, and in 1774 published ‘Mémoire sur la probabilité des causes par les évènemens’, in which he stated the principle’:

在贝叶斯之外,拉普拉斯已经开始研究一种从结果回到原因的概率方法,并于 1774 年发表了关于事件产生原因的概率的论文《Mémoire sur la probabilité des causes par les évènemens》,他在其中阐述了原则。

- If an event can be produced by a number n of different causes, then the probabilities of these causes [given the event are to each other as the probabilities of the event given the causes], and the probability of the existence of each of these is equal to the probability of the event given the cause, divided by the sum of all the probabilities of the event given each of these causes.

- 如果一个事件可以由 n 个不同的原因产生,那么在给定事件的情况下,这些原因的概率彼此等同于在给定原因的情况下事件的概率,并且这些原因中的每一个存在的概率等于在给定原因的情况下事件的概率除以在给定这些原因中的每一个的情况下事件的所有概率的总和。

This statement of inverse probability is only valid when the causes are all equally likely. It was not until later than Laplace generalised this result to handle causes with different prior weights.

这个逆概率的陈述只有在所有的原因都同样可能的情况下才有效。直到后来,拉普拉斯才将这一结果推广到处理具有不同先验权重的原因。

1781

In 1781, Price visited Paris and told the Secretary of the French Royal Academy of Sciences, the Marquis of Condorcet, about Bayes’ discovery. This information eventually reached Laplace and gave him confidence to pursue his ideas in inverse probability. The trouble with his theory for going from an effect back to a cause was that it required an enormous number of calculations to be done to arrive at an answer. Laplace was not afraid of a challenge, however, and invented a number of incredibly useful techniques (for example, generating functions and transforms) to find an approximate answer. Laplace still needed an example application of his method that was easy enough for him to calculate, yet interesting enough to garner attention. His chosen data sample was composed of babies. Specifically, his sample comprised the numbers of males and females born in Paris from 1745 to 1770.

1781 年,普莱斯访问了巴黎,并向法国皇家科学院秘书孔多塞侯爵讲述了贝叶斯的发现。这一信息最终传到了拉普拉斯那里,使他有信心追求他的反概率思想。他的理论从结果回到原因的问题是,它需要进行大量的计算才能得出答案。然而,拉普拉斯并不惧怕挑战,他发明了许多令人难以置信的有用技术(例如,生成函数和变换)来寻找一个近似的答案。拉普拉斯仍然需要一个他的方法的应用实例,这个实例对他来说足够容易计算,但又足够有趣,以引起人们的注意。他选择的数据样本是由婴儿组成的。具体来说,他的样本包括 1745 年至 1770 年在巴黎出生的男性和女性的数量。

This data was easy to work with because the outcome was binary – the child was recorded as being born a boy or girl – and was large enough to be able to draw conclusions from it. In the sample, a total of 241,945 girls and 251,527 boys were born. Laplace used this sample and his theory of inverse probability to estimate that there was a probability of approximately $10^{-42}$ that the sex ratio favoured girls rather than boys.

这些数据很容易处理,因为结果是二分类问题——孩子出生时被记录为男孩或女孩——而且数据足够大,足以从中得出结论:在样本中,总共有 241,945 名女孩和 251,527 名男孩出生。拉普拉斯利用这一样本和他的逆概率理论估计,性别比偏向于于女孩而不是男孩的概率约为 10-42。

On the basis of this tiny probability, he concluded that he was as ‘certain as any other moral truth’ that boys were born more frequently than girls. This was the first practical application of Bayesian inference as we know it now. Laplace went from an effect – the data in the birth records – to determine a probable cause – the ratio of male to female births.

根据这个微小的概率,他得出结论,他“像任何其他道德真理一样肯定”男孩比女孩出生得更频繁。 这是我们现在所知道的贝叶斯推理的第一个实际应用。 拉普拉斯从一个结果——出生记录中的数据——确定了一个可能的原因——男性与女性出生的比例。

Later in his life, Laplace also wrote down the first modern version of Bayes’ mathematical rule that is used today, where causes could be given different prior probabilities:

在他的晚年,拉普拉斯还写下了今天使用的第一个现代版本的贝叶斯数学规则,其中原因可以给予不同的先验概率

On the left-hand side, P denotes the posterior probability of a given cause given an observed event. In the numerator on the right-hand side, H is the probability of an event occurring given that cause, p, is the a priori probability of that cause. In the denominator, S. denotes summation over all possible causes, and H and p now represent the corresponding quantities to those in the numerator, but for each possible cause.

在左侧,P 表示在观察到的事件中某一特定原因的后验概率。在右边的分子中,H 是指在该原因下事件发生的概率,p 是该原因的先验概率。 在分母中,S.表示对所有可能的原因进行求和,H 和 p 现在表示针对每个可能的原因,与分子中的量相对应的数量

History has been unfair to Laplace and Price. If they were alive today, the theory would, no doubt, be known as the Bayes–Price–Laplace rule.

历史对拉普拉斯和普莱斯是不公平的。 如果他们今天还活着,这个理论无疑会被称为贝叶斯—普莱斯-拉普拉斯定理。